Jewelry casting is the process of forming jewelry by pouring molten metal into a mold, where it solidifies into the desired shape. This technique – often done via lost-wax casting – is fundamental in modern jewelry manufacturing, enabling makers to create multiple pieces with complex designs efficiently. In fact, the majority of jewelry today (especially in mass production) is made through casting rather than entirely by hand fabrication. Casting allows for high detail and consistency, making it possible to bring intricate or custom designs to life repeatedly with uniform quality. By using casting, jewelers can produce everything from one-of-a-kind bespoke pieces to large production runs, bridging ancient craftsmanship with modern technology to meet the demands of today’s market.

Show Table of Contents

Table of Contents

History of Metal Casting

Metal casting is one of the oldest metalworking methods, with origins tracing back thousands of years. The earliest known metal castings date to around 3200 BC in Mesopotamia, where simple molds were used to shape bronze tools and ornaments. Lost-wax casting (also called investment casting) emerged independently in ancient civilizations – evidence shows it was practiced by 3,500–3,000 BC in regions like Sumer (ancient Iraq) (Lost-wax casting – Wikipedia). Over 6,000 years, this technique spread across continents, employed for jewelry, sculpture, and ritual art. Notably, it was widely used in West African cultures by the mid-2nd millennium (e.g. the Benin bronzes) and throughout history for fine jewelry and idols.

As metallurgy advanced (through the Iron Age and beyond), casting processes improved, allowing larger and more complex objects to be made. In the industrial era, mechanization and new materials revolutionized casting – the process became essential for mass-producing metal parts. By the late 19th and early 20th century, jewelry industries embraced casting (aided by dental investment casting techniques), making it possible to create jewelry at scale for a growing market. Today, jewelry casting remains a blend of ancient art and science, integral to both artisan studios and high-tech manufacturing, carrying forward a rich legacy of craftsmanship.

Types of Precious Metals Used in Casting

Casting can be done with almost any metal, but in jewelry the focus is on precious metals and their alloys:

- Gold (14K, 18K): Gold is a premier choice for casting and is typically used in alloyed forms like 14-karat (58.5% gold) or 18-karat (75% gold). Pure 24K gold is very soft, so mixing it with copper, silver, or other metals increases strength while retaining gold’s luster. Both 14K and 18K gold are common in jewelry, with 14K being slightly harder and more durable, and 18K prized for its richer yellow color. Gold alloys can also produce white or rose gold (with nickel/palladium or copper content), all of which can be cast. Gold’s malleability and relatively lower melting point (~1,648°F / 898°C for 14K) make it well-suited for intricate cast designs.

- Silver: Sterling silver – an alloy of 92.5% silver with 7.5% copper – is the standard for cast silver jewelry. Pure silver (99.9%) is too soft for most jewelry, but sterling is durable yet still melts at a manageable temperature (~1,640°F / 893°C). Silver flows well into molds and captures fine detail, making it popular for casting rings, pendants, and art pieces. One challenge is that silver’s copper content can form fire-scale (oxidation) during casting, a layer of copper oxide that may require pickling (acid cleaning) to remove. Despite this, silver remains one of the most used casting metals due to its beauty and affordability.

- Platinum: Platinum is a precious metal valued for its rarity, strength, and pure white color. Jewelry-grade platinum is usually 90–95% pure (marked 900 or 950 platinum), alloyed with a bit of ruthenium, iridium, or other metals for workability. Platinum has a very high melting point (~3,215°F / 1,768°C), which makes casting it more challenging – it requires higher temperatures and often a controlled environment. Specialized equipment (like induction vacuum casting machines) are used to melt and cast platinum, as this metal must be poured at extreme heat and under an inert or vacuum atmosphere to prevent oxidation. The result, however, is exceptionally durable jewelry with a luxurious heft. Platinum casting has become more accessible with modern tech, but it remains a niche requiring expertise.

- Other Metals: Jewelers also cast with other precious metals such as palladium and palladium-based alloys, which belong to the platinum group. Palladium (used in some white gold alloys or on its own at ~95% purity) has a high melting point and produces a durable, white metal similar to platinum. Some jewelry, particularly fashion or costume pieces, may be cast in bronze, brass, or other base metals – these are easier to cast (lower melting points like ~1700°F for bronze) and cheaper, though they lack the intrinsic value of precious metals. In recent times, rose gold (a gold-copper alloy), white gold (gold alloyed with nickel or palladium), and even steel or titanium have been used in jewelry casting, though steel/titanium require industrial methods not typical in small jewelry studios. Overall, gold, silver, and platinum (and their alloys) remain the pillars of jewelry casting, chosen for their workability, beauty, and consumer preference.

The Metal Casting Process: Step-by-Step Guide

Jewelry casting (particularly lost-wax casting) involves a series of steps to go from a design idea to a finished metal piece. Below is a detailed breakdown of each stage of the casting process:

Wax Model Creation

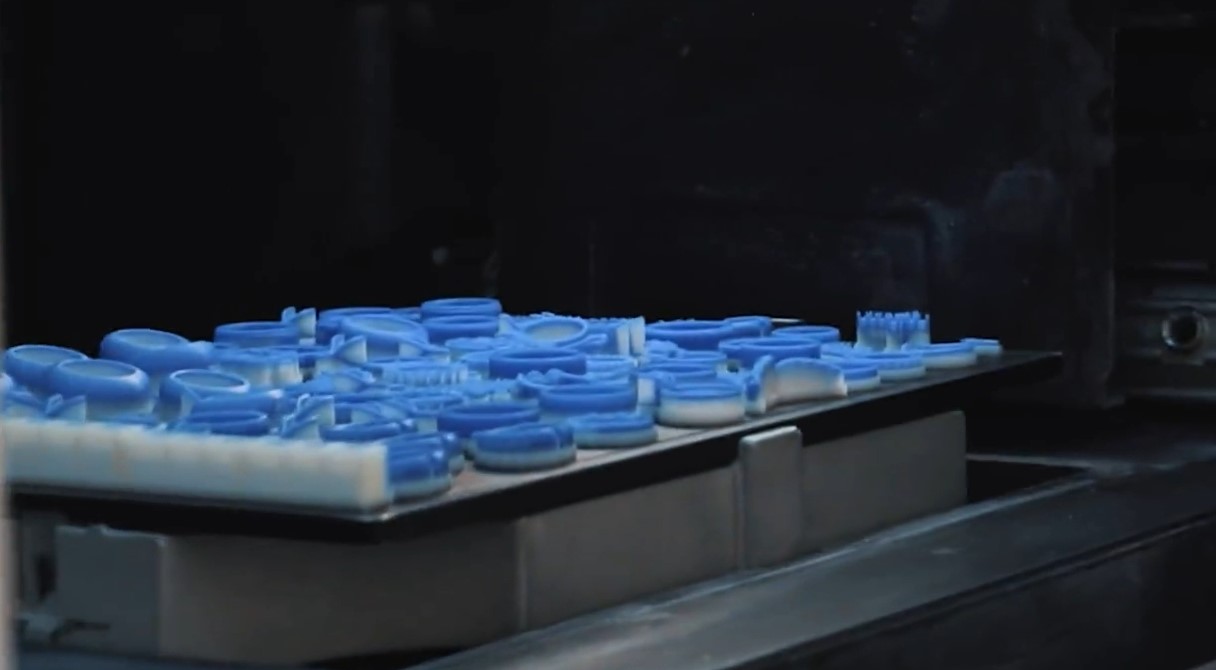

Wax models attached to a central sprue base, forming a “tree” for casting multiple pieces simultaneously. The casting process begins with creating an exact model of the jewelry piece in wax. This wax model can be hand-carved or formed using various methods: some artisans sculpt wax by hand, while others produce the model via CAD design and 3D printing in castable resin or wax. For multiple copies, wax models are often replicated using rubber molds and wax injection. Once a wax pattern is made, a sprue (wax rod) is attached to it to serve as a channel for metal. Jewelers commonly mount one or several wax models on a wax sprue base to form a wax tree (multiple pieces arranged on a central stem) so that they can cast many items in one go. Meticulous attention is given to this stage: the wax must accurately represent the final design (including any prongs or engraving), and sprues must be attached at strategic points (usually the thickest part of the model) to ensure proper metal flow and minimize shrinkage voids. Any imperfections in the wax – bumps, scratches, or asymmetry – would later appear on the metal, so model-making requires precision and often a quality check for flaws (Guide to jewelry manufacturing – Empire Casting House). A well-crafted wax model is the blueprint for a successful casting.

Investment (Mold Creation)

Once the wax model (or wax tree) is ready, it needs to be encased in a mold material to form a negative impression of the design. This stage is called investing. The wax model/tree is placed inside a metal flask (a hollow cylindrical container). A liquid plaster-like slurry called investment is mixed and poured into the flask, covering the wax model completely. Investment powder is typically a special gypsum (plaster) mixed with silica and other ingredients that can withstand high heat. It is mixed with water to a specific ratio – often to a consistency of heavy cream – ensuring it flows around every detail of the wax pattern. To avoid air pockets (which could cause defects on the jewelry surface), the flask with the liquid investment is usually vacuumed or vibrated, pulling out any trapped air bubbles. The investment then hardens (sets) around the wax model, forming a solid mold. This step essentially creates a one-time-use mold (investment molds are broken after casting, hence “expendable”). Best practices here include careful measuring of investment and water, proper mixing under vacuum, and allowing the invested flask to cure and dry (often for at least 1–2 hours) before the next step. At this point, the wax model is fully encased in a hardened investment material, ready for wax removal.

Burnout Process

Burnout is the process of eliminating the wax from the hardened investment mold, creating a hollow cavity in the shape of the jewelry. The flask containing the invested wax is placed in a special kiln (burnout oven) and heated on a specific schedule. Initially, the oven is kept at a low temperature (~300°F / 150°C) to dry out any residual moisture and gently melt some wax. As the temperature rises, the wax melts out of the mold and eventually burns off completely (hence “lost wax”). A typical burnout cycle might ramp the kiln up to around 1350°F (730°C) and hold it for a couple of hours. This high heat incinerates any wax traces, leaving a clean void in the investment. By the end of burnout, the interior of the mold precisely matches the wax model that was “lost”. The result is a heat-proof mold with an empty jewelry-shaped cavity (and channels where the sprues were). Burnout also strengthens the investment mold by baking it. It’s critical that burnout is thorough – any remaining wax or carbon can contaminate the metal casting or cause defects. Investment molds are often heated for several hours in total. Once burnout is complete, the flask is kept hot (often 900–1100°F, depending on the metal being cast) until the moment of casting. Having the mold hot is important to ensure the metal remains liquid as it fills the cavity and to avoid thermal shock to the investment (Lost-wax casting – Wikipedia). After burnout, the mold is ready to receive the molten metal.

Metal Melting and Pouring

In this stage, the chosen metal (gold, silver, platinum, etc.) is melted and poured into the prepared mold. The metal (often in the form of casting grain or scrap pieces) is placed in a crucible – a heat-resistant container – and brought to its melting point. Jewelers may use a gas-air torch or an electric induction heater to melt the metal. Once the metal is molten and at the proper casting temperature, the crucible is aligned with the opening of the hot flask (the opening left by the main sprue). Using gravity or force, the molten metal is poured into the mold, flowing through the channels and into the jewelry cavity (Guide to jewelry manufacturing – Empire Casting House). In jewelry casting, two main methods assist the flow: centrifugal casting, where the flask is spun at high speed to fling metal into every crevice, and vacuum casting, where a vacuum pulls the metal down into the mold. Both methods serve to ensure the metal fills even fine details before solidifying (centrifugal force can push metal into fine filigree, while vacuum removes air and gas that might impede flow). For instance, in a centrifugal casting machine, the crucible and flask are part of a rotating arm: once the metal is molten, the arm is released, spinning rapidly so that metal is forced into the mold with considerable pressure. In vacuum casting, the flask sits in a vacuum chamber; when metal is poured, a vacuum pump creates suction that draws the metal in, minimizing air bubbles. Either way, within a few seconds the mold cavity is filled with liquid metal, replicating the original wax model’s shape. This step is dramatic and crucial – temperature control is key (overheating can cause oxidation or porosity, underheating can lead to incomplete filling). Often, a bit of extra metal is kept molten above the mold opening (forming a button) to feed the casting as it cools and shrinks. Once the mold is filled, the casting is left to cool for a short period.

Cooling and Mold Removal

After pouring, the metal inside the mold begins to cool and solidify (this happens fairly quickly for small jewelry pieces, usually within a few minutes). The flask is then allowed to cool enough to handle, or in many cases, it is quenched – submerged in water – to speed up cooling and to break away the investment. Quenching a hot plaster investment in water causes it to disintegrate: the sudden cooling and steam pressure crumbles the plaster, freeing the cast metal object inside. For example, a flask of silver or gold may be quenched in water about 5–10 minutes after casting, once the metal has just solidified but the investment is still hot and fragile. The thermal shock shatters the investment mold, and agitation in water helps wash off the debris. What emerges is the “raw” casting – the tree of metal jewelry pieces still attached to the central sprue tree. If the flask is not quenched (for instance, some casters let platinum or certain investments cool slowly), the investment is broken out by hand. In that case, one might use tools or media blasting to remove the mold material. Either way, the once-invested jewelry pieces are now metal and ready for cleaning. At this stage, the cast jewelry will have a rough, dull appearance, often covered in a residue of investment material and oxidation. The pieces are cut off from the central sprue tree using a saw or shears. Each piece, now separate, proceeds to the finishing steps.

Cleaning and Finishing

The cast metal jewelry, though in the correct shape, requires significant finishing work. Cleaning involves removing any remaining investment plaster, pickling off oxides, and cutting away the sprues. Typically, the cast pieces are placed in an acid bath (a “pickle” solution, like diluted sulfuric or a sodium bisulfate solution) which dissolves oxides and investment residues, bringing the metal to a clean surface. Once cleaned, the sprue nubs (the points of attachment) and any excess metal are removed with snips or by grinding. The casting will have minor roughness or seams from the process, so it undergoes several finishing techniques: filing, sanding, and polishing. Jewelers use files to gently reshape areas and remove any protrusions or casting skin. Abrasive wheels or sandpaper clean up surfaces and prepare them for polishing. Any small pits from casting (if present) can be filled or filed down. At this stage, care is taken to check for porosity or defects – if a casting defect is severe (like a large void), the piece might be rejected or repaired if possible. Assuming the cast is sound, the piece is then polished using polishing wheels, brushes, or tumbling media to achieve the desired luster. Fine details may be sharpened or engraved if needed, and textures can be applied. If the design includes stones, the casting is now ready for stone setting once the metalwork is all cleaned up. In summary, finishing transforms the rough cast item into a piece of jewelry with smooth surfaces and shine. It’s the final but crucial step: casting gets the piece made in metal, and finishing makes it beautiful and wearable.

(The above step-by-step describes lost-wax investment casting, by far the most common method in jewelry making. There are other casting techniques and variations, which we will cover next.)

Jewelry Casting Techniques

Several casting techniques are used in jewelry production, each with its own process and applications. The primary methods include lost-wax casting, as well as alternative or supplementary methods like sand casting, centrifugal casting, vacuum casting, and 3D printing-assisted casting. Here we explain each and how they relate to jewelry:

Lost-Wax Casting (Investment Casting)

Lost-wax casting is the main method described above and is the backbone of modern jewelry casting. In this technique, a wax model of the piece is made, then encased in investment material, burnt out, and filled with molten metal – “losing” the wax in the process. Lost-wax casting is prized for its precision: it can reproduce extremely fine details, thin walls, and complex shapes that would be difficult to fabricate by other means. Because the investment mold captures the exact shape of the wax, jewelers can achieve high-resolution results, even for filigree or ornate designs. This method is versatile and can be used for small delicate pieces or larger ones (up to a certain size). It also allows casting multiple pieces in one flask (using wax trees). Lost-wax casting is ancient (over 5,000 years old) yet continually refined; it remains the most widely used casting technique in jewelry making. It’s suitable for virtually all metals (gold, silver, platinum, etc.) by adjusting investments and equipment. The term investment casting is often used interchangeably, especially in industrial contexts. In jewelry, lost-wax casting enables both one-off custom creations and mass production – after an initial model is made, rubber molds can produce many wax copies that are cast to yield dozens or hundreds of identical pieces. The key advantages of lost-wax casting are its high precision, excellent surface finish, and design flexibility. A potential downside is the cost and time of making each mold (since investment molds are single-use), but for high-detail work and quality, lost-wax is unparalleled. Essentially, if a design demands intricate detail or a high-quality finish, lost-wax casting is the go-to method.

Sand Casting

Sand casting is one of the oldest casting methods, wherein a pattern (model) is pressed into a special sand mixture to create a mold. In jewelry sand casting, a two-part flask is used: the design is embedded into sand, the flask is split to remove the original model, and then reassembled to pour metal into the cavity. While sand casting is heavily used in industrial contexts for large metal parts, it can be applied on a smaller scale for jewelry or artistic objects. The process is relatively simple and uses reusable mold material (sand can be reclaimed), making it cost-effective for certain applications. However, sand casting generally cannot capture as fine detail as lost-wax casting. The sand grain texture often imparts a rough surface to the metal, and the process isn’t suitable for very thin or delicate shapes. In jewelry, sand casting might be used for bold, less intricate designs – for example, heavy signet rings, ingots, or rustic designs – where a slightly rough, hand-wrought aesthetic is acceptable or even desirable. It’s also useful when only one or a few pieces are needed without the overhead of creating wax models and investments. The precision is lower (higher tolerances and more finishing work usually required). Advantages of sand casting include low mold cost (just sand and a box, no expensive investment or equipment) and the ability to cast larger pieces that might be impractical with investment (sand molds can be made much bigger). For jewelers, sand casting can be a creative alternative for certain styles or a learning tool to understand casting basics. But if a project requires high detail or a smooth finish, sand casting would not be the best choice – it’s generally reserved for simpler, larger, or stylistically rough pieces. In summary, sand casting offers simplicity and low cost, but at the expense of fine detail and surface quality.

Vacuum Casting

Vacuum casting refers to the use of a vacuum to assist the casting process, typically as part of lost-wax investment casting. In vacuum casting, the flask (investment mold) is placed in a vacuum chamber when metal is poured. The vacuum sucks air from the mold, helping the molten metal to fill every nook and cranny of the mold without air pockets or back-pressure. This method is particularly favored for achieving defect-free castings with high detail and for casting metals that oxidize or have high melting points. The vacuum not only removes air (preventing bubbles and porosity) but can also reduce oxidation by drawing out atmospheric gases. Jewelry vacuum casting machines often combine a melting crucible on top and a vacuum chamber below the flask. When the metal is ready, gravity starts the pour and the vacuum pulls the metal through. Features & Benefits: Vacuum casting yields very high-quality results; the castings are smooth and consistent, with minimal porosity. It is also relatively safe and easy to operate for small studios – there is no need for a spinning arm (as in centrifugal), and multiple flasks can be cast sequentially with one machine. Vacuum casting works well for gold and silver, and with specialized machines, for platinum (some machines even have an inert gas and vacuum environment for platinum). It provides more control over pouring and solidification, which is beneficial for complex or filigree pieces. Many professional casting houses use vacuum casting for large batches, as it scales well and ensures uniform results across many pieces. In short, vacuum casting is a modern technique that improves upon traditional gravity-pour casting by eliminating air and creating a controlled environment, thus achieving excellent detail and quality in jewelry castings.

Centrifugal Casting

Centrifugal casting (often simply called “spin casting” in jewelry) is another widely used technique to force metal into a mold. As described earlier, it employs a centrifuge: the metal is melted in a crucible that is part of a rotating arm, and upon release, the whole crucible+flask assembly spins at high speed, flinging the molten metal into the mold with centrifugal force. This method has been a mainstay in jewelry casting for many decades (the classic spring-driven centrifugal casting machines are common in jewelry workshops). Features & Benefits: Centrifugal casting excels at forcing metal into very fine details and thin sections, because the spinning action actively pushes the liquid metal into all parts of the mold. It often results in dense castings and can reduce certain types of porosity, since the metal is literally pressed into place quickly. Spin casting is efficient and relatively fast – the mold is filled almost instantly, reducing the chance of metal cooling prematurely. It is versatile in terms of metals: jewelers cast gold, silver, bronze, and even platinum (with special high-torque centrifugal machines) using this method. Centrifugal casting equipment ranges from small manual machines (that you wind up and release) to larger motorized units. For a small shop, a centrifugal setup can be more affordable than a vacuum machine. Use Cases: Centrifugal casting is great for one-off casts or small batches. Typically, one flask is cast at a time (per spin), so for production runs multiple cycles are needed. It’s particularly popular in custom or artisan jewelry settings. Some complexities (like very large flasks or extremely intricate multiple trees) might be less suited for small centrifugal units, but generally spin casting is a robust all-purpose method. The main considerations are safety and consistency – a poorly balanced arm or improper locking can cause spills (molten metal centrifugal spills are dangerous), so training and precautions are important. In conclusion, centrifugal casting offers jewelers a reliable way to achieve high-detail, high-density castings quickly. It remains one of the most common casting methods, especially in smaller-scale operations, complementing vacuum casting as an equally effective approach in skilled hands.

3D Printing-Assisted Casting

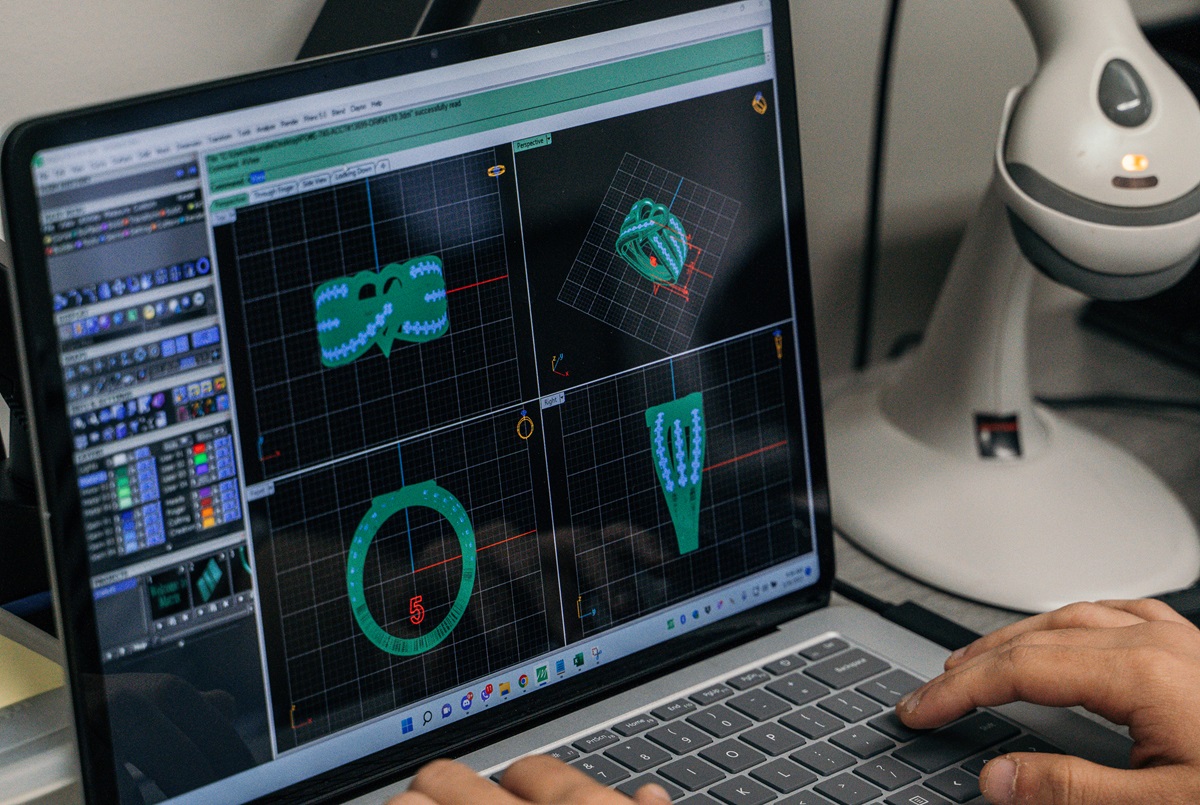

3D printing has become a game-changer in the casting world by dramatically improving the model creation stage. In 3D printing-assisted casting, jewelers use CAD (Computer-Aided Design) software to design the piece digitally, then produce the model using a 3D printer (usually a high-resolution resin printer) instead of hand-carving wax. The printed model (made from a castable resin or wax-like material) serves the same purpose as a traditional wax model: it gets invested and burned out so metal can be cast in its place. The casting step itself is still typically lost-wax (or lost-resin) using vacuum or centrifugal methods to actually cast the metal. The innovation here is how the pattern is made: 3D printing allows for extremely complex geometries, including designs that would be near-impossible to carve by hand (for instance, interlocking parts, very intricate lattice or texture, etc.). It also enables rapid prototyping – a designer can print multiple iterations quickly to test designs before casting. Modern castable resins burn out cleanly with proper burnout schedules, similar to wax. Advantages: 3D printing-assisted casting merges traditional casting with digital precision. Designers can modify a CAD model and re-print a new pattern within hours, making the development process much faster and more flexible than hand-carving wax. It’s possible to print trees of multiple models as well. Production can be scaled by printing dozens of patterns for investment in one batch. The digital approach also allows easy replication: once a design is in CAD, it can be printed repeatedly or in multiple sizes. Many jewelry manufacturers now use 3D printed wax/resin patterns for casting, especially for custom designs or when creating master models for molding. Considerations: The 3D printing equipment has a cost, and one must ensure the resin used is truly ash-free on burnout (specialized castable resins are formulated for this). Burnout cycles often need to be adjusted for resin (usually a longer, cooler initial phase to avoid rapid expansion). But these challenges are well understood, and numerous casting houses successfully cast thousands of 3D printed patterns. Another frontier is direct 3D metal printing (like SLM/DMLS – directly printing metal objects without casting), but that is a different process altogether, currently used for some high-end one-off pieces or industrial parts. In the context of typical jewelry workshops, 3D printing is a complement to casting, not a replacement – it provides new ways to create castable models. In summary, 3D printing-assisted casting leverages modern technology to enhance the age-old lost-wax process: jewelers get the best of both worlds – the freedom to design complex, custom pieces digitally and the proven reliability of investment casting to realize them in precious metal.

Comparison of Casting Methods

Each casting method has its own strengths and ideal uses. The table below compares the major techniques discussed – lost-wax, sand, vacuum, centrifugal, and 3D printing-assisted – in terms of precision, cost, suitable metals, and typical applications in jewelry making.

| Casting Method | Precision & Detail | Cost & Equipment | Suitable Metals | Common Applications |

| Lost-Wax Casting (Investment) | High precision – captures fine details and smooth surfaces with minimal finishing. Intricate designs and thin sections achievable. | Moderate cost – requires one-time investment molds and kiln; can cast multiple pieces per mold (efficient for batches). Equipment like burnout oven and casting machine needed. | Nearly all jewelry metals – gold (all karats), silver, platinum (with special setup), palladium, brass/bronze etc. | Most jewelry pieces – The default method for fine jewelry and mass production. Best for detailed designs, consistent quality, and medium-scale production. |

| Sand Casting | Low precision – rougher surface finish, less detail fidelity; not suitable for very thin or filigree parts. Requires more post-cast finishing. | Low cost – uses inexpensive sand molds (reusable sand); minimal equipment (no burnout oven needed). Good for one-off pieces or experimental work. | Many metals possible (gold, silver, bronze, brass, aluminum, etc.), but not ideal for high-melt metals like platinum in small setups. Often used with silver, brass, or gold for simpler forms. | Simple or heavy designs – used for rustic-style jewelry, large pieces, or when a textured/antique look is acceptable. Also used in teaching or hobby contexts for basic casting. |

| Vacuum Casting (lost-wax variant) | High detail quality – vacuum eliminates air bubbles, yielding smooth, defect-free castings. Ensures complete filling of mold details. | Higher equipment cost – requires a vacuum casting machine; can be justified for production. Offers efficient casting of multiple flasks with consistent quality. | All precious metals – excellent for gold and silver; with advanced machines can cast platinum (using vacuum with inert gas). Also good for other metals that benefit from atmosphere control (e.g., avoiding oxidation). | Professional production – used in many casting houses and larger jewelry workshops for consistent, high-quality results. Ideal for filigree, high-detail pieces, and medium to large batch production. |

| Centrifugal Casting (lost-wax variant) | High precision – centrifugal force drives metal into fine details and thin sections quickly. Produces dense castings with good detail replication. | Moderate cost – centrifugal machines range from simple spring-driven units (affordable) to more advanced. One flask cast at a time, but casting cycle is quick. Requires operator skill and safety precautions. | All common jewelry metals – widely used for gold, silver, bronze. Platinum can be cast with high-speed centrifugal machines designed for the higher temperature. | Custom and small-scale casting – perfect for small workshops, artisans, and custom jewelry where pieces are cast one flask at a time. Used for casting rings, pendants, etc., especially when quick turnaround is needed. |

| 3D Printing-Assisted Casting (hybrid process) | Very high potential detail – depends on 3D printer resolution. Can create extremely complex or delicate models that are then cast via lost-wax process. Final casting detail is as good as investment casting (since it is investment casting) – the advantage is in model complexity. | Upfront cost in printer – requires a 3D printer and materials. However, saves labor in model making and enables rapid prototyping. Casting equipment costs similar to lost-wax (since that’s the casting method used). | All castable metals – the technology affects the model, not the metal. So gold, silver, platinum, etc. can all be cast from 3D printed patterns (with appropriate burnout process). | Prototyping & complex designs – used for custom jewelry and innovative designs that would be hard to carve by hand. Great for producing masters for new designs, one-of-a-kind intricate pieces, or quickly making multiple different models for casting in one batch. Now common in both small studios and large manufacturers for increasing design capabilities. |

Key: Lost-wax vs Sand casting shows a trade-off between detail and cost. Vacuum and Centrifugal are not opposing methods but rather different ways to achieve a quality cast – vacuum provides a controlled environment, whereas centrifugal provides physical force; both aim to fill the mold completely. 3D printing is a digital augmentation to the casting process, expanding what can be cast, but ultimately the metal quality and precision still rely on investment casting principles.

(In practice, jewelers may use a combination of these methods: for example, designing with CAD and 3D printing a wax model, then casting it via lost-wax vacuum casting. The “best” method depends on the project’s requirements for detail, volume, and metal.)

Advantages and Challenges of Jewelry Casting

Like any manufacturing process, jewelry casting comes with a set of advantages as well as challenges. Understanding these can help jewelers optimize their process and troubleshoot issues.

Advantages of Jewelry Casting:

- Intricate Designs: Casting allows for the creation of highly intricate and complex shapes that would be difficult or impossible to achieve by fabrication (bending/cutting metal). Designs with filigree, organic forms, or detailed engravings can be directly cast from a wax model. This gives designers tremendous freedom in creativity.

- Efficiency & Reproduction: Once a model (or mold) is prepared, casting is an efficient way to reproduce pieces. Multiple identical wax models can be cast together, yielding many copies in one batch. This is ideal for mass production – hundreds of units of a design can be made with consistent results. It’s far quicker than carving each piece from metal.

- Material Conservation: Investment casting can be very material-efficient. The process yields near-net-shape pieces, meaning little extra metal is wasted. Sprues and buttons (excess metal) can be melted down and reused. Compared to carving from solid metal stock, casting has minimal scrap – design flexibility with minimal material waste.

- Cost-Effective for Volume: For large production runs or even small batches, casting often lowers labor costs per piece. One skilled craftsperson can cast many pieces at once, whereas hand-making each would require far more time. This scalability makes jewelry more affordable and accessible. Casting was “necessitated by the rapid growth of the jewelry industry” as an economical method to meet demand.

- Consistency & Repeatability: Casting from the same mold or model ensures each piece comes out with the same shape. This uniformity is crucial for lines of jewelry where customers expect identical items (e.g. ring sizes, earring pairs). With proper technique, casting produces repeatable quality with only minor finishing variances.

- Versatility of Alloys: Casting accommodates a wide range of alloys. Jewelers can cast different colors of gold (yellow, white, rose), sterling silver, brass, etc., using the same process, simply by changing the metal in the crucible. Modern casting grain alloys are often formulated to fill well and reduce defects, further improving outcomes.

- Integration with Technology: The casting process benefits from modern tools – CAD design, 3D printed patterns, and improved casting machinery – which make it even more powerful. This synergy of old and new techniques means casting continues to improve in precision and capability.

Challenges and Limitations:

- Porosity and Defects: One of the most common issues in casting is porosity – tiny holes or voids in the metal caused by shrinkage or gas entrapment. Improper sprue design, inadequate degassing of metal, or too rapid cooling can lead to shrinkage porosity (often seen as tiny pits when polishing). Gas porosity can occur if the metal or mold has trapped air that doesn’t escape. Jewelers must carefully design sprues and control temperatures to mitigate porosity. Even with best practices, some micro-porosity can occur and may need filling or might weaken the piece if severe.

- Requires Skill and Equipment: While casting streamlines production, it also demands knowledge and specialized equipment. A jeweler must understand mold-making, burnout cycles, metal melting points, etc., and invest in tools like kilns, crucibles, and casting machines. Mistakes at any step (e.g., incomplete burnout, overheating metal) can ruin a piece or mold. There is a learning curve and need for experience to consistently get good results.

- Initial Model/Mold Work: Before you can cast, you need a model or pattern – creating this (by carving wax or designing a CAD model) is an upfront effort. If a design changes, you often have to make a new wax. For each new piece or style, the casting workflow from scratch is required. Thus, for one-off pieces, casting can actually be more labor-intensive than directly fabricating in metal, because you must make the wax and mold first.

- Surface Finish & Shrinkage: Cast surfaces, even when good, are typically slightly rougher than forged or milled metal. They often require polishing and finishing to achieve a high shine. Fine details might need sharpening after casting. Additionally, metal shrinks as it cools (e.g., ~1-2% for gold alloys), so the final piece will be slightly smaller than the wax model. This shrinkage must be accounted for in the design (model made a bit larger) and can occasionally distort dimensions if not uniform.

- Quality Control Issues: If casting is done in large batches, there’s a risk that some pieces may have defects (like a misrun where metal didn’t fill a section). Identifying and sorting out defective castings is necessary, which adds to labor. Casting multiple pieces together (on a tree) means if something goes wrong (e.g., investment cracked), it could potentially ruin the whole batch. Hence, careful process control is needed.

- Loss of Uniqueness: In a more artistic sense, critics of casting note that it can reduce the “handmade” uniqueness of jewelry. Since many pieces can be reproduced from one model, pieces might lack the slight variations that come with entirely hand-built items. This is a consideration for one-of-a-kind high-end jewelry, where clients value that a piece was hand-forged or fabricated individually. However, skilled finishing and customization can bring uniqueness back to cast pieces (through hand-texturing, etc.).

- Material Constraints: Some metals are tricky to cast. For example, white gold often contains nickel, which can be prone to porosity if not cast correctly (some white gold alloys are “deoxidized” to help). Sterling silver can get fire-scale (oxidation of copper) which requires additional steps to remove or prevent (like casting in an oxygen-reduced environment or using special alloys). Platinum casting, as mentioned, needs very high temperatures and often induction equipment – not every jewelry studio can accommodate that, meaning many jewelers outsource platinum casting to specialized facilities.

- Environmental/Safety Hazards: Casting involves open flames or high-power furnaces, handling molten metal, and potentially hazardous materials (investment powder contains silica, which can be dangerous to inhale; burnout ovens can emit wax fumes). Proper safety gear (respirators, gloves, face shields) and ventilation are a must. Mistakes can cause serious accidents (burns, fires). So the process carries more risk than some other jewelry-making techniques, requiring a disciplined approach to safety.

Despite these challenges, the benefits of jewelry casting typically far outweigh the drawbacks for most production needs. With experience, jewelers learn to minimize defects and ensure quality. Modern casting grains and equipment have also addressed many traditional problems (for instance, adding deoxidizers in gold alloys to reduce gas porosity, or using vacuum/pressure to all but eliminate air entrapment. Casting, when done right, produces high-quality, beautiful jewelry efficiently. It’s an indispensable part of the industry – but it does require care and skill to master.

Modern Innovations in Jewelry Casting

The jewelry casting process has continually evolved, and recent innovations are making it more precise and efficient than ever. Here are some modern advancements that are transforming casting:

- 3D Printing and Digital Design: As discussed, CAD software and 3D printing have revolutionized how jewelers create casting models. Designers can now digitally sculpt incredibly complex pieces and produce castable resin or wax models with ease. This dramatically speeds up product development and enables geometries that traditional carving might not achieve. 3D printing technology keeps improving, with higher resolution printers (like LCD, DLP, and SLA printers capable of 20–50 micron detail) and better castable materials. This means the gap between the designer’s vision and the cast result is smaller than ever – what you model on screen is faithfully realized in metal. The hybrid of traditional craftsmanship and cutting-edge tech is the new norm: artisans combine their skills with digital tools to push boundaries while maintaining quality.

- Advanced Casting Machinery: Modern casting machines integrate automation and precise controls to improve outcomes. For example, there are casting systems with programmable temperature control, vacuum and pressure cycles, and even robotic handling. Automated vacuum casting machines can regulate the melting temperature exactly and then apply vacuum/pressure in a controlled sequence, ensuring each casting is done under optimal conditions. Induction heating in machines provides fast, even melting of metal with less oxidation (because the metal can be melted in a crucible under a protective atmosphere). Induction vacuum casting is now a standard for platinum and high-end casting: the metal melts via induction coil and the machine casts it under vacuum or inert gas, greatly reducing contamination and achieving very high quality. These machines have made what used to be extremely challenging (like casting platinum or palladium) much more accessible and reliable.

- Improved Alloys and Materials: Metallurgists have developed special casting alloys for jewelry that cast better than old formulations. For instance, certain gold alloys are labeled “de-ox” or “casting grain” – they include additives like silicon or zinc that help prevent oxygen porosity and yield a cleaner cast. Sterling silver alloys like argentium or other modified sterling reduce fire-scale and cast with less porosity. Even investment powders have seen improvements: some investments are formulated to handle the different thermal expansion of 3D printed resins, and others are made for the extreme heat of platinum casting. There are also washable investments for easier cleanup. All these material innovations contribute to higher success rates in casting and finer finished quality.

- Vacuum and Pressure Casting Tech: The introduction of vacuum/pressure combination casting (also known as vacuum-assisted pressure casting) is another innovation. In these systems, after the metal is melted (often in a chamber), the flask is placed and the machine first pulls a vacuum and then applies a positive pressure to force metal into the mold even more aggressively. This dual approach can virtually eliminate shrinkage porosity and ensure even the most detailed molds fill completely. It’s particularly useful for very detailed or large items.

- Quality Control & Simulation: High-tech solutions are now used to predict and catch issues before they happen. Casting simulation software can model how metal flows into a mold and where it might solidify too quickly or shrink, allowing designers to adjust sprue arrangements or temperatures digitally before actually casting. Some larger manufacturers use X-ray or CT scanning on sample castings to check internal integrity, fine-tuning their processes. While these are more on the industrial side, they trickle down to jewelry as well, especially for critical work (like expensive gemstone settings or high-value pieces where failure is not an option). Modern casting labs may also employ sensors and thermal imaging to monitor casts in real time.

- Automation and Efficiency: For high-volume jewelry production, automation is key. We now see automated wax injection machines (to make wax models in rubber molds quickly), robotic arm sprue cutters, and even automated systems that build casting trees (there is software that can arrange digital models optimally for 3D printing or mold making (Improving Mold Design with Cimatron and Metal Additive … – YouTube)). Some companies have streamlined casting so much that a design can go from CAD to a finished cast piece in 24 hours. Multiple casting lines, each controlled by computers, can run simultaneously with minimal human intervention aside from setup. This significantly boosts productivity – a far cry from the fully manual casting of the past.

- Direct Metal 3D Printing (Additive Manufacturing): While not casting in the traditional sense, it’s worth noting the emergence of direct metal 3D printing as an alternative manufacturing method. Technologies like Selective Laser Melting (SLM) or Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) can “print” jewelry directly in metals like gold, platinum, or steel by fusing metal powder layer by layer. This bypasses casting entirely for those pieces. However, these methods are currently expensive and have their own limitations in surface finish and density. They are used for some unique pieces and prototypes. For now, lost-wax casting is still more economical and practical for most jewelry production, but in the future, some synergy or combination of these technologies might further change how jewelry is made.

In summary, technology is continuously enhancing jewelry casting. CAD and 3D printing improve the input (the models), while advanced machinery and materials improve the output (the cast metal). These innovations lead to better castings with fewer defects, higher detail, and faster turnaround. They also lower the skill barrier a bit – for instance, a modern casting machine with digital controls can help a novice achieve decent results by following programmed steps. Nonetheless, expert human oversight is still crucial. The melding of traditional know-how with modern tech defines today’s casting: a seasoned jeweler armed with 21st-century tools can achieve remarkable feats, bringing creative visions to life in metal with precision and efficiency unimaginable in decades past.

Best Practices for Successful Metal Casting

To consistently achieve high-quality results in jewelry casting, certain best practices should be followed at each step of the process. Here are key recommendations and tips from industry experts:

- Start with a Flawless Model: “Trash in, trash out” applies to casting – any flaw in your wax model will appear in the metal. Take time to create clean, detailed wax patterns and inspect them for defects or asymmetry before investing. Repair any scratches or pits in the wax, and ensure attachments (like prongs or channels) are secure. If using multiple waxes on a tree, position them so they won’t distort when the investment is poured (e.g., not too close together). A well-prepared wax (or resin print) is the foundation of a good casting.

- Design Sprues and Trees Wisely: Proper spruing is critical to avoid casting issues like shrinkage porosity or incomplete fills. Use sprue channels that are thick enough and short enough to feed your castings. Attach sprues to the heaviest section of the wax model so that as the metal solidifies, the thinner sections freeze first and the thicker sections can draw metal from the sprue (this prevents hollow spots). For multiple items on a tree, arrange them evenly around the sprue base to allow uniform metal flow. Avoid very long or thin sprues which can freeze off too early. If casting a large piece, provide additional feeders or reservoirs. In short, ensure the metal has a clear path and adequate supply to every part of the mold.

- Use High-Quality Investment and Mix It Properly: Follow the manufacturer’s instructions for your investment powder. Weigh the powder and measure the water precisely for each batch – consistency in the mix yields consistent molds. Mix under vacuum if possible to eliminate air bubbles, or at least vibrate the flask after pouring to bring up bubbles. Pour investment slowly down the side of the flask to avoid trapping air against the wax. Once poured, vacuum again if equipment is available. Make sure the investment is fresh (moisture or age can affect it) and appropriate for your metal (for example, use a high-temp investment for platinum). Let the investment mold set for the recommended time (usually ~ investment solidifies in 10-15 minutes, but do not put it into burnout immediately – most recommend at least a 2-hour curing time). This allows the investment to gain strength and reduces risk of cracks or steam expansion.

- Implement a Proper Burnout Cycle: A controlled burnout schedule ensures all wax is eliminated and the mold is preheated correctly. Typically, ramp the oven slowly: e.g., hold at around 300°F to allow wax to melt and drain (with the flask ideally inverted or in a kiln with a tray). Then raise to an intermediate temperature (~700°F) to burn off residue, then up to final burnout temperature (between 1350°F–1450°F for gypsum-based investments) and hold for at least an hour or two. Ensure the kiln has good ventilation so the wax can burn out cleanly (oxygen supply). Do not shortcut the burnout time – leftover wax or ash can cause investment breakdown or porosity in the metal. If using resin models, consult resin-specific burnout schedules (they often need a slower ramp to avoid expanding too fast and cracking the investment). Before casting, drop the oven temperature to the proper casting temperature for the flask, typically somewhere between 900°F and 1100°F for gold/silver flasks (lower for large items, higher for fine items). Proper burnout not only removes the wax but also ensures the mold is hot enough (and free of moisture) so the metal flows well.

- Melt the Metal Correctly: Use a clean crucible dedicated to the type of metal you’re casting (to avoid contamination). If reusing metal, make sure to add some fresh casting grain to rejuvenate the alloy – reusing 100% scrap repeatedly can lead to oxide buildup and brittleness. Flux can be used for melting silver or bronze to help prevent oxidation, but avoid over-fluxing as it can absorb important alloy elements. Heat the metal to the right pouring temperature: too cold and it won’t fill, too hot and it may cause excessive oxidation or investment damage. For example, cast 14K gold around 100-150°F above its liquidus temperature, and sterling silver similarly above its melting point. If using a torch, watch the metal – pour when it’s fully molten with a mirror-like surface and just as a slight glow or vapor starts to come off (indicating it’s hot enough). If using an induction or electric melter, rely on temperature settings and confirm via a thermocouple if possible. Avoid overheating (superheating by hundreds of degrees “just in case”) as this increases shrinkage porosity and gas absorption. Skim any debris off the molten metal surface before pouring.

- Choose the Casting Method Suited to the Piece: If you have a vacuum casting setup, ensure the vacuum pump is functioning well and that the seal on the flask is tight. For centrifugal, make sure the machine is properly wound and secure, and always stand in a safe position (with the protective arm between you and the spinning arm). Preheat the crucible if using a centrifugal machine with an external crucible. Use appropriate sling weight or arm speed for the metal mass. Essentially, use your equipment as intended: vacuum for large trees or very detailed pieces (or when casting many flasks sequentially), centrifugal for quick casts of single flasks, etc. Each requires slightly different prep, but both need the flask at proper temperature and the metal molten and clean. Follow any specific machine guidelines – e.g., in vacuum casting, some recommend briefly releasing then re-applying vacuum after pour to dislodge any bubbles, or in centrifugal, waiting a specific time before quenching.

- Quench at the Right Time (if applicable): Quenching too early or too late can affect the metal. As a rule, for gold and silver alloys, quench once the metal has just solidified but the flask is still quite hot (usually a dull red glow) – often around 5 minutes after casting. This rapid cooling can help reduce certain types of metal segregation and makes investment removal easier. However, for some metals (like many platinum or high-karat gold alloys), slow cooling in-flask is recommended to avoid thermal shock or to achieve desired metallurgical properties. Know your alloy: for example, nickel-white gold benefits from quenching to improve its malleability, whereas some 18K red gold might form a more brittle structure if quenched too quickly (so let it cool more). Always wear safety gear when quenching – the steam and investment fragments can erupt. Use a large bucket of water and gently submerge the flask with tongs, don’t drop it in.

- Clean and Pickle Properly: After retrieving the cast pieces, remove all investment residues. Use a warm pickle solution (sparex or similar) to dissolve oxides – this will brighten the castings and reveal the true metal color. Make sure not to put steel tools in the pickle (it can plate copper onto pieces). Rinse thoroughly after pickling. Stubborn investment bits can be removed with a water jet or ultrasonic cleaner. If a piece shows fire-scale (a deep purplish oxide stain on sterling silver), it might need more pickling or abrasive removal; consider using a de-oxidizing solution or lightly sanding if needed. Cleaning is not just aesthetic – leftover investment can hide in crevices and later fall out (potentially during stone setting or customer wear), so ensure pieces are fully clean before further work.

- Inspect Castings and Address Issues: It’s a best practice to examine each casting before proceeding to finishing or stone setting. Look for any defects: tiny surface pits (porosity), incomplete fill areas, cracks in the metal, or misalignment. Hold rings up to light to see if any pinholes go through, or cross-section thick parts if you suspect internal porosity. Casting evaluation is important to catch problems early. Minor porosity on the surface can often be polished out or filled by soldering, but significant voids may require filling with solder or metal laser-welding, or recasting the piece entirely. If multiple pieces show the same flaw, it indicates a process issue – for instance, if all pieces on one side of a tree didn’t fill, perhaps the sprue was insufficient or investment not thoroughly burned out in that area. Use these observations to adjust your next casting (learning and improving continuously). It’s better to spend a moment on QC now than to discover a problem during final polishing or, worse, have a customer discover it.

- Master Finishing Techniques: Although finishing comes after casting, good finishing work can salvage a borderline casting or elevate a good casting to perfection. Use appropriate files (e.g., needle files for small areas) to remove sprue stubs without gouging the piece. If using a flex shaft or grinder, be gentle – you just want to smooth the casting skin, not reshape the piece heavily (assuming your casting was true to the model). Progress through sanding grits for a smooth surface, then polish using tripoli (cutting compound) and rouge (polishing compound) or modern abrasive media. For pieces with intricate details, consider tumble polishing or smaller buff tips. The goal is to eliminate any remaining evidence of the casting process (like parting lines or surfaces left slightly rough) and bring out the metal’s luster. Finishing is also your last chance to detect issues like soft metal (if a piece is significantly softer than expected, it might have not alloyed right) or structural problems.

- Maintain Equipment and Safety: A often overlooked “best practice” is simply taking care of your tools and yourself. Keep your burnout oven calibrated – an off-temperature oven can ruin molds (investment can break down if held too hot for too long). Ensure your vacuum pump oil is changed and there are no leaks in hoses. For centrifugal machines, regularly check for wear in the spring or cradle. Clean crucibles to avoid mixing alloys. Work in a well-ventilated area, especially during burnout (burning wax/plastic produces fumes) and melting (flux fumes, metal vapors). Wear protective gear: leather apron, face shield when casting, heat-resistant gloves, and a respirator when mixing investment (investment dust silica can cause serious lung disease). By keeping the workspace safe and equipment in top shape, you reduce the risk of accidents and miscasts.

By following these best practices – from model creation to final polish – jewelers can greatly increase their casting success rate. In essence, attention to detail at every step, adherence to proven procedures, and continuous learning (adjusting methods based on results) are the hallmarks of successful metal casting. With practice, casting becomes a dependable process, opening up countless possibilities in jewelry creation.

Jewelry casting is both an art and a science – a process rooted in ancient technique yet vital to modern jewelry production. In this guide, we covered how casting transforms a wax model into a precious metal masterpiece, the history of how metal casting came to be so essential, and the many facets involved: from selecting the right metal alloy to choosing an appropriate casting method for the job. We explored lost-wax casting in depth (the jeweler’s go-to method), as well as alternatives like sand casting, and the technologies (vacuum, centrifugal, 3D printing) that enhance the casting workflow.

Each casting technique offers distinct advantages, and understanding their differences helps in deciding the best approach for a given project – whether it’s achieving the highest detail, minimizing cost, or scaling up production. We also addressed the advantages that make casting attractive (like efficiency and the ability to create intricate designs) and the challenges that must be managed (such as porosity and the need for skilled execution). Modern innovations continue to push the boundaries of what casting can do, making it more accessible and reliable without losing the charm of the craft.

In summary, jewelry casting remains a cornerstone of the industry because it provides a versatile way to bring creative visions to life in metal. From one-off custom rings to mass-produced collections, choosing the right casting technique and following best practices can yield beautiful, durable pieces that meet the highest standards of quality. By mastering the casting process, a jeweler gains the power to literally cast their ideas into reality. As technology evolves and techniques are refined, jewelry casting will only become more powerful – but at its heart it will always be about that magical moment of pouring molten metal into a mold and later revealing a work of art. Embracing both the traditional knowledge and the modern improvements in casting ensures the best outcomes. Ultimately, the art of jewelry casting – with all its steps and nuances – enables the creation of exquisite jewelry that adorns us, tells stories, and carries forward an age-old legacy of craftsmanship in a contemporary way.